Do viruses cause Cancer? | Virology Series

In medical training, the idea that viruses can cause cancer is taught as fact. Unfortunately, that claim is devoid of historical context, biological plausibility, as well as confirmatory evidence.

Background Information

The following information is adapted from various historical accounts, including those documented by professor Peter Duesberg of UC Berkeley.

The discovery of viruses began as vectors for infectious disease, but slowly morphed into a field of unproven conjectures. For decades we have been looking for ways to blame cancer on viruses.

At first, we used viruses to account for acute illness that seem to coexist in space and time (AKA outbreaks). They clustered around a geographic location, at a specific point in time. Then, we moved unto identifying novel pathogens, then seasonal pathogens. Eventually we got to harmless skin lesions (herpes, pox). As infectious diseases became far less prevalent - in large part due to the advent of sanitation and access to clean water - there was less and less for virology to diagnose & treat.

The post-polio-era virologists were looking for a new game. Cancer was on the rise. So, they began applying their tools to find the hypothetical cancer-causing virus.

In the Beginning

In 1905, there was a reception for Robert Koch (of Koch's Postulates) who had been awarded the Nobel Prize. German Emperor Wilhelm II noted to have said to Koch:

My dear professor, now you must find the cancer-bug.

...but in german.

Virologists faced two major obstacles:

Cancer is not contagious, but viral disease is.

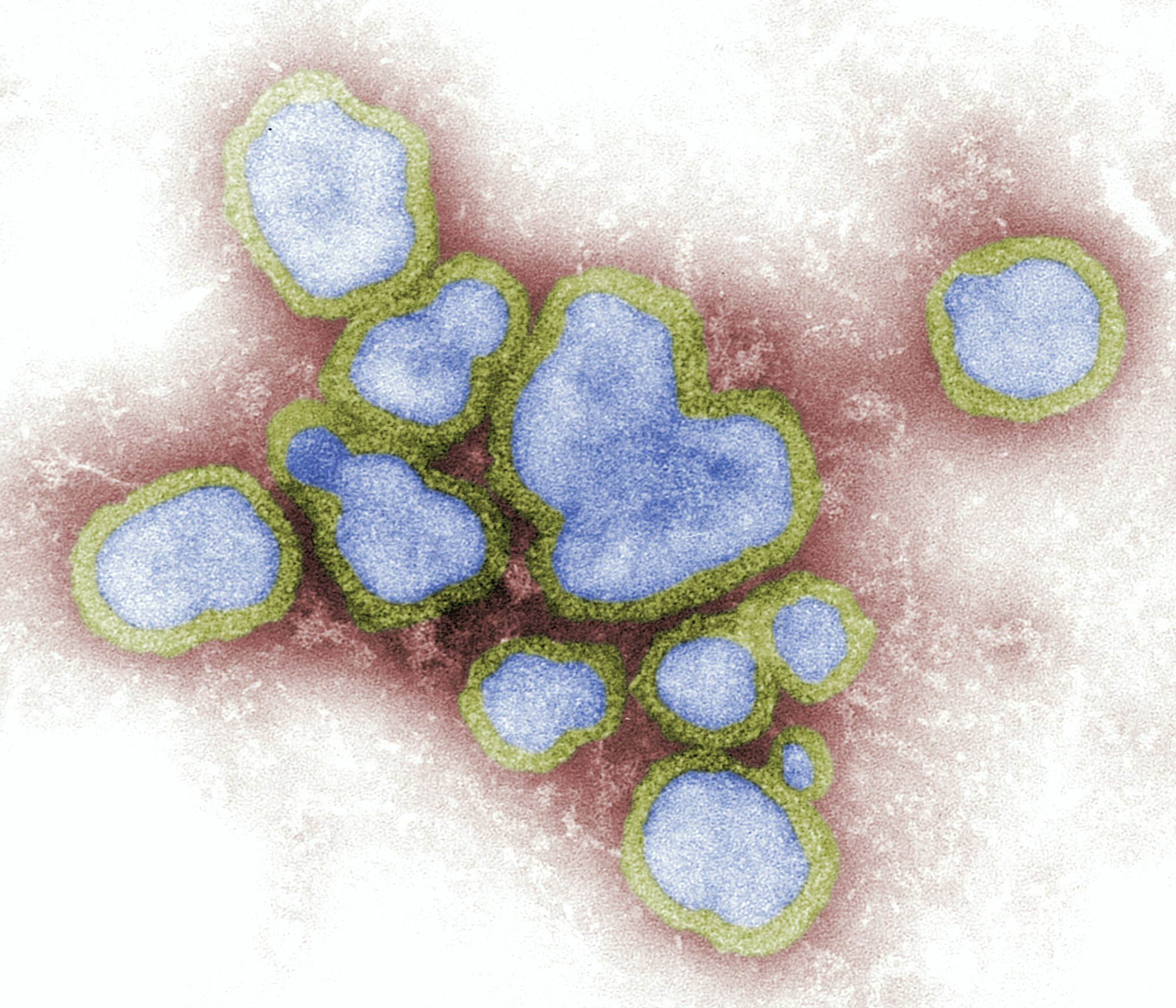

Viruses reproduce by entering a cell, using its resources to replicate, then break out of the cell - destroying it.

Cancer is a disease in which cells continue to live & propagate uncontrolled. These cells change their behavior to become more aggressive, less cooperative, and invasive of boundaries. As these cells consume your body, like insatiable parasites, you can die.

If a virus destroy cells in their lifecycle, how could it possibly cause them to become immortal & cancerous?

Think about this another way:

If the objective of viruses is to replicate and propagate across time...why would a virus evolve to induce a cellular state (cancer) that is so resource consumptive, that there would be none left for the viral genes that are trying to self-propagate.

In fact, you could make the case that once a cell becomes cancerous - unrestricted growth & replication - it marks the end of the virus. The cancer would deplete the resources required to propagate the virus. Thus, any virus that did cause cancer would take itself out of the evolutionary tree.

As biotechnology got more sophisticated, the virologists began experimenting with them in their hunt for cancer. This seemed to solve their problem (of irrelevance) and enabled them to seize control of the field of cancer research.

They claimed that:

If you wait long enough, the virus would progress from infection to cancer. Anywhere up to 50+ years after the initial infection.

They postulated a defective virus that was unable to multiply (keeping the cell alive), but still able to cause cancer...inventing a unique class of viruses.

To their credit, virologists made a perfectly legitimate observation of a rare event. A fluke of nature virus caused tumor growth in some extraordinarily rare instance, in a susceptible animal.

Enter Rous Sarcoma Virus

The first tumor-virus was observed in 1908.

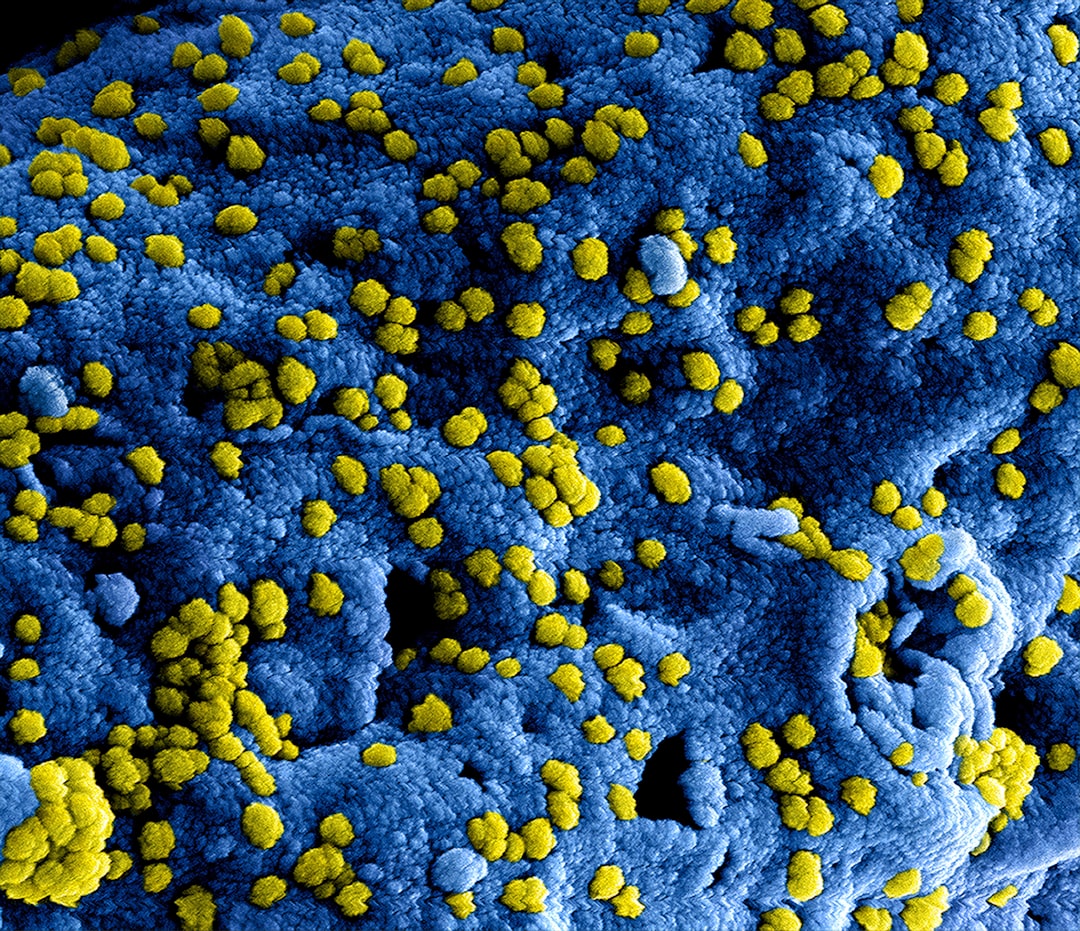

Vilhelm Ellerman & Oluf Bang discovered that something tiny enough to pass through a bacterial filtration system - assumed to be a virus - caused leukemia in newly infected chickens. Peyton Rous isolated filtrate from a chicken with a solid tumor, and discovered that it caused rapidly growing tumors in other chickens within days of infection - named this Rous Sarcoma Virus (RSV)

RSV is a retrovirus. Retroviruses propagate through the continued existence of the host cell lineage. The more harmless they are, the more successful - because the host lives a long and healthy life. The continued survival of the host cell opens the possibility of potential carcinogenic activity, if even through random mutation.

But, RSV was mostly ignored. We could not find it in humans because human cancers are not contagious - unlike some animal cancers. These viruses would only affect special strains of mice that had been intentionally weakened by generations of inbreeding.

These conditions can cause disease & cancer spontaneously - no need for the virus.

Furthermore, these viruses could not cause cancer in mice from the wild.

Decades later, the virologists would seize upon these scattered experimental observations as precedent to claim that harmless viruses cause cancer.

Funding starts rolling in...

In the late 1930s, 24 grants were distributed by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in its first 5 years in existence - only 2 went to virus research. Over the next several decades, the NCI kept cancer virology alive. As the virologists took senior positions at the NCI, they used the Rous Sarcoma Virus as justification for funding this line of work.

Ludwik Gross took a position at the Bronx VA, and began research on a virus that caused leukemia in mice. He stumbled upon the same problem - it caused cancer in the sick inbred lab-mice, not the healthy wild mice.

Other researchers quickly began replicating Gross' work. Sarah Stewart discovered a second virus that caused tumors throughout the body - named polyomavirus.

As others bandwagonned, the challenge became self-evident:

Find a virus that causes cancer in humans.

The Hunt Is On

By the 1970s, over a dozen viruses were isolated from mice with leukemia...all of which were as meaningless as the first. Nonetheless, the NIH kept distributing funds. This had the effect of drawing a lot of attention from virologists and grad students.

At some point, people suggested that if they could create a vaccine for the virus, they could prevent cancer!

Wendell Stanley was the first Nobel Prize winner for the study of viruses. In the 1956 National Cancer Conference he stated:

...we should assume that viruses are responsible for most, if not all, kinds of cancer...design and execute our experiments accordingly...no reason to shy away from giving consideration to viruses as causative agents in cancer...

Oncologists knew all too well that tumors rarely contained detectable virus. Why would it? It's not expressing anything other than what the cell needs to replicate & grow without restriction. That's what cancer does.

Carleton Gajdusek became popular in the 1960s because the cancer-virus crowd found his unproven concept of an 'unconventional' slow virus quite attractive. It really helped their virus-cancer case. They needed to rationalize the absence of detectable virus.

Andrew Lwoff suggested the possibility of a 'dormant' virus. He too received a grant from the NCI and got to work.

Despite all of the efforts described above, scientists could find no active virus in tumors.

The fundamental problem remained that, even in the lab setting of viruses inserting themselves into specific cells - by the very nature of resource competition - these viruses would shortly cease to exist.