Lessons from History | 2. Scurvy & Infection

In the 16th century, scurvy was observed to be a dietary problem. This was forgotten and as recently as the 1900s, scurvy was thought to be an infectious disease.

What is Scurvy?

Scurvy is a disease caused by a lack of vitamin C in the diet. Vitamin C is also known as Ascorbic Acid.

Long before vitamin C was isolated (1930s), various individuals noticed that scurvy could be cured.

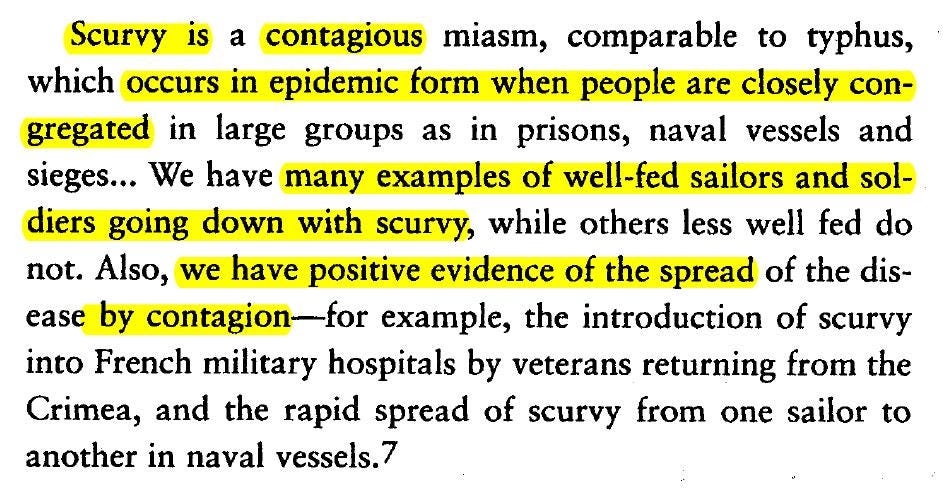

The concept of contagion, and outbreaks, is older than Robert Koch’s discovery of disease-causing bacteria. The historic significance of contagious outbreaks obscured the discovery of what causes scurvy for hundreds of years.

Early Investigations

Scurvy was first described by physicians in the 1500s, including Ronsseus & Echthius. Ronsseus was an advocate of a dietary hypothesis. Echthius observed outbreaks of scurvy in a monk monastery, and concluded the disease was infectious.

Sir Richard Hawkins, a British admiral, encountered scurvy among sailors on a long voyage in 1593. Upon reaching Brazil, he discovered that oranges would cure the condition. Unfortunately, even he felt obligated to blame unsanitary shipboard conditions.

Around the same time, a Frenchman named Francois Pyrard attributed scurvy to a lack of cleanliness. He insisted that "it is very contagious, even by approaching or breathing another's breath."

Pyrard ironically had also discovered the curative power of citrus fruits.

Infection more concerning than deficiency

The discovery of dietary remedies was forgotten (as was admiral Hawkins), and the infectious view continued to prevail.

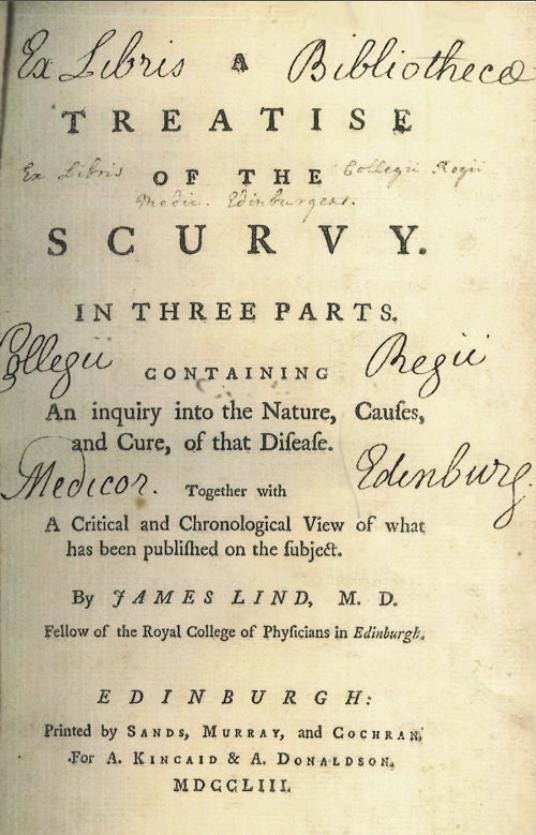

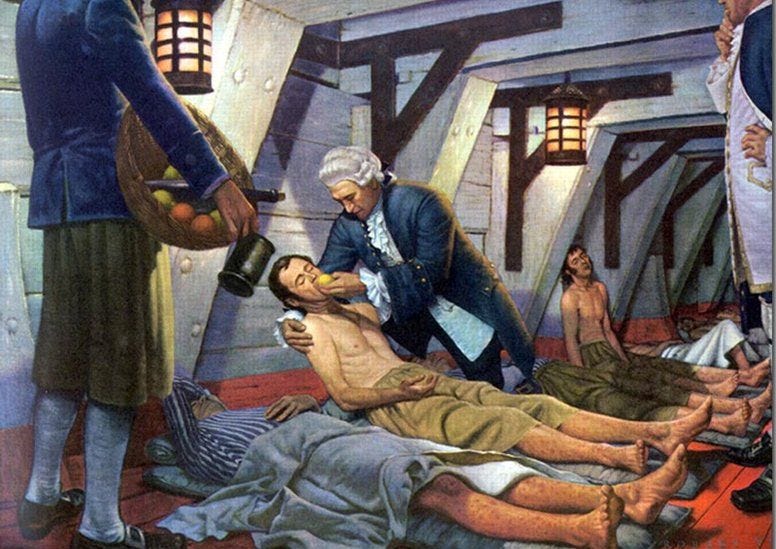

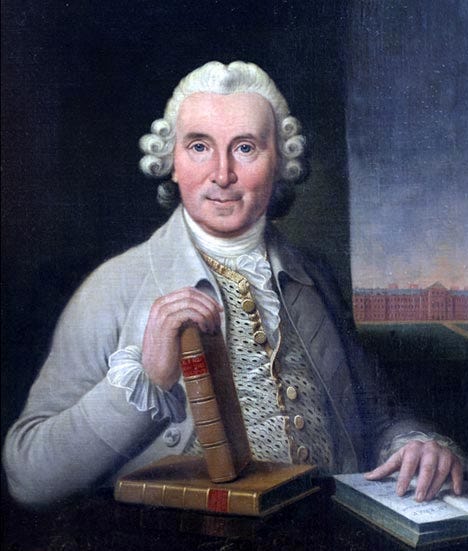

In 1734, an outbreak of scurvy occurred on a voyage of a British ship. This event motivated a British Naval surgeon, James Lind, to begin experimenting. After years of research, Lind concluded that a substance found in citrus fruits was key to both the prevention and cure of scurvy. Lind published his findings in a book entitled Treatise Of The Scurvy in 1753. He was roundly rejected by the British medical establishment for forty years.

Not until 1795, was lemon juice provided to sailors.

In the same period (1769), English captain James Cook discovered that vegetables and citrus fruits worked. Cook also insisted on hygienic practices and fresh air - further confusing the significance of their findings.

Infection prevails

Negligence, combined with the rise of bacteria-hunting in the late 1800s, led scientists to ignore these early discoveries.

Jean-Antoine Villemin, of the Paris Academy of Medicine, was the first to demonstrate that tuberculosis was an infectious disease. Villemin became a passionate advocate of germ theory in general, and in 1874 began debating against the widely accepted view that diet was somehow responsible for scurvy.

Outbreak of disease is not sufficient evidence for an infectious cause. A clustering of disease merely suggests a shared environment.

It was previously observed that fresh meat contained a substance which prevented scurvy. In 1899, British explorer Frederick Jackson decided to flip this hypothesis on its head. He insisted that it was a toxin in old meat which caused scurvy - not a vitamin in fresh meat which prevented it. Admittedly, an interesting thought.

Joseph Lister, who popularized the use of antiseptic in surgery, had become president of the Royal Society of London around this time. He wished to see new research on scurvy in light of recent microbe discoveries.

Doubt begins to creep

Microbe-hunting not only distracted scientists from discovering vitamin C, but also caused epidemics of scurvy.

Louis Pasteur's technique for sterilizing milk (pasteurization) had spread throughout Europe and America. Popular because the microbe-hunters convinced the public of the importance of hygiene.

Unfortunately, the pasteurization process destroyed the vitamin C in milk, which caused outbreaks of scurvy in children.

Doubling-down

Unwilling to admit their mistake, the American Pediatric Association issued a report on childhood scurvy in 1898. They concluded that a toxin produced by bacteria was the real cause of the scurvy epidemic.

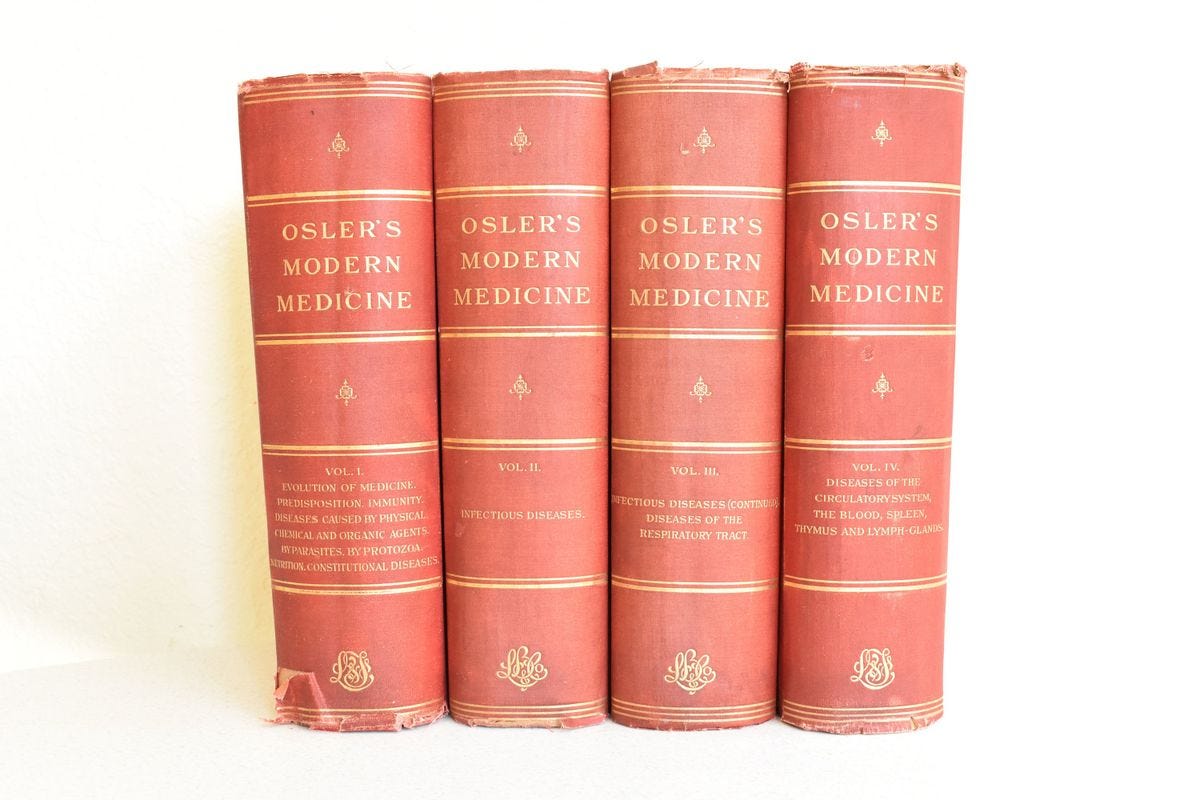

The medical community would not let go of the microbial hypothesis. Sir William Osler is one of the most celebrated physicians in modern history. While recognizing the role of diet in scurvy, he wrote in Osler’s Modern Medicine (1907) that an unidentified microbe must cause the sickness.

During World War I, a group of scientists isolated a different bacterium from scorbutic guinea pigs. The bacilli found in the animals were then injected into healthy guinea pigs. Some of them developed symptoms resembling scurvy. The bacteria could never be found in the blood of the newly infected animals. Additionally, the blood from a sick animal would not make another animal sick when injected - violating two of Koch’s postulates.

Another report at that time proposed that scurvy could be transmitted through lice. Unencumbered, researchers argued they had found the scurvy-causing germ.

Many in Russia believed bacteria to be the cause, as did surgeons in the European military. In 1916, a German doctor examining Russian soldiers suffering from scurvy, blamed their sanitation.

Truth Prevails

The germs blamed for scurvy failed to meet Koch's postulates. Adherence to these foundational principles of microbiology could have prevented much of the wasted effort.

Scientists were busier trying to emulate Koch's success, rather than his rigorous logic.

The microbe-hunting era did not permanently derail the search for vitamin C, which was isolated in the 1930s.

In 1953, C.P. Stewart, professor of clinical chemistry at University of Edinburgh, summarized the scurvy disaster in his appropriately entitled book Lind’s Treatise on Scurvy:

Lesson: Humility

James Lind wrestled with a medical community that was not ready for the dietary deficiency hypothesis. The instinctual fear of contagion would not allow for the novel observation that this ‘outbreak’ was caused by lack in diet.

Lind conducted a rigorous investigation. He determined that not only did citrus fruit consumption prevent scurvy, but it also cured the disease after you "caught it."

I urge you to seriously consider his position, as he was dismissed for 40 years. Lind had the humility to recognize that we did not know the cause.

It took "modern medicine" nearly 200 years to confirm Lind's discovery. Vitamin C. Ascorbic acid. Of the scorbutic disease.

Arrogance will be our undoing

James Lind’s published findings were ignored. In the meantime, countless lives suffered as a result of ignorance.

But, don’t let this distract from the audacity of James Lind.

Today, this would be akin to asserting that the cause of liver cirrhosis is not alcohol consumption nor a viral infection.

Instead, consider that liver cirrhosis is associated with a diet lacking pomegranate. Further, that there is some substance contained within pomegranate which would prevent and cure liver cirrhosis.

It may very well be that thousands, if not millions, will suffer because we failed to heed such a suggestion. Not to mention all the money wasted on research, testing, and intervention.

The arrogance of man knows no bounds. The potential damage is likewise unlimited.

Follow me on Twitter @RemnantMD

Reminds me of the Vitamin D epidemic we are facing today. There is enough observational and other evidence regarding its value but its significance continues to be under recognized and undermined.

Folk medicine knew how to cure scurvy. Indian tribes knew. Many captains knew. But the learned doctors kept shooting it down, over and over, while people died.

The British Royal Navy began to give out citrus in the late 18th century. But this article shows that it still hadn't sunk in by the time WWI rolled around. Same with blood letting. Doctors were still pushing it in the early 20th century... though it was shown to be harmful 75 years prior. Mindboggling. Hubris!