INSIGHTS | 21. Ray Peat Pt. II - Cancer

Ray Peat is a Professor of Physiology with an almost cult-like following. Not for religious zealotry, per se, but rather his opinions on the causes and remedies to illness.

In Part I we introduced who Ray Peat is and some of the content of his thought on physiology and disease.

In this installment, we will look at his thoughts on cancer and contrast them with modern medical thought.

Once it is accepted that cancer is a systemic disease, and that a tumor…is something more than a collection of defective cells, very different therapeutic approaches can be considered.

-Ray Peat

When considering differences in thought, it is often the case that certain details are misunderstood or misinterpreted.

In the case of cancer, it may very well be that our fundamental understanding of what cancer represents…is wrong.

But, how deep do we have to dive to correct our course?

What is Cancer?

It may be that we have fundamentally misunderstood cancer. Similar to other medical specialties, despite decades of research and billions in funding, we still do not have a model which sufficiently describes & predicts the behavior of cancer.

Fiat medicine definition:

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body.

The core dogma of cancer is that tumors arise from a single cell which develops (by various mechanisms) the ability to grow without restraint. This framing of cancer has led to the inevitable rise in the use of genetics to describe the disease. Genetics has since become incorporated into almost all medical specialties, but none as much as oncology - the cancer specialty.

The genetic framework implies that the changes that occur in a cancerous cell are causally related to specific mutations and are thus irreversible. This inevitably has led to a strategy of destroying all cancer cells as the primary mode of treatment.

And when that doesn’t work…we believe that ‘salting the earth’ - aka chemotherapy and radiation - would prove effective.

This is where we are today in modern medicine.

Cancers are diagnosed under microscope, growth is assessed by serial imaging, and treatment consists primarily of:

Mutilation

Chemotherapy

Radiation

An exercise in killing the ‘intruder’ before killing the host.

What is wrong with this Model?

Recently, I had an opportunity to work with and learn from a renowned Ivy League neuropathologist. He is well past retirement and has a wealth of experience, working closely with neurologists, neurosurgeons, and neuroradiologists.

We began discussing glioblastoma, one of the most common and aggressive forms of brain cancer. It is well understood within the medical community that glioblastoma is incurable. No matter how much of the tumor and surrounding brain you remove, it comes back.

No matter how much chemotherapy and radiation you use after surgically removing the mass - it still comes back.

To quote the neuropathologist:

“You can never remove enough brain to prevent it from recurring.”

I asked him:

“What if our framework that tumors arise from a single cell, and spread outward is wrong. What if the tumors we visualize on imaging & pathology slides are a convergent phenomenon? What if the nervous system overall is diseased in such a way that at this location in the brain you can see a tumor?”

His answer completely floored me.

Here is a man who has seen more brain cancer than I ever will.

His reply:

That is an interesting question, and I have no idea how we could even go about answering it.

As his trainees interrupted to insist that cancers arise from a single cell, he cut them off…

He’s right. We have no ground truth to confirm that our current interpretation is the correct one. It could very well be a convergent phenomenon.

His response told me everything I needed to know to continue pursuing this line of thought.

Unto some of Peat’s critique:

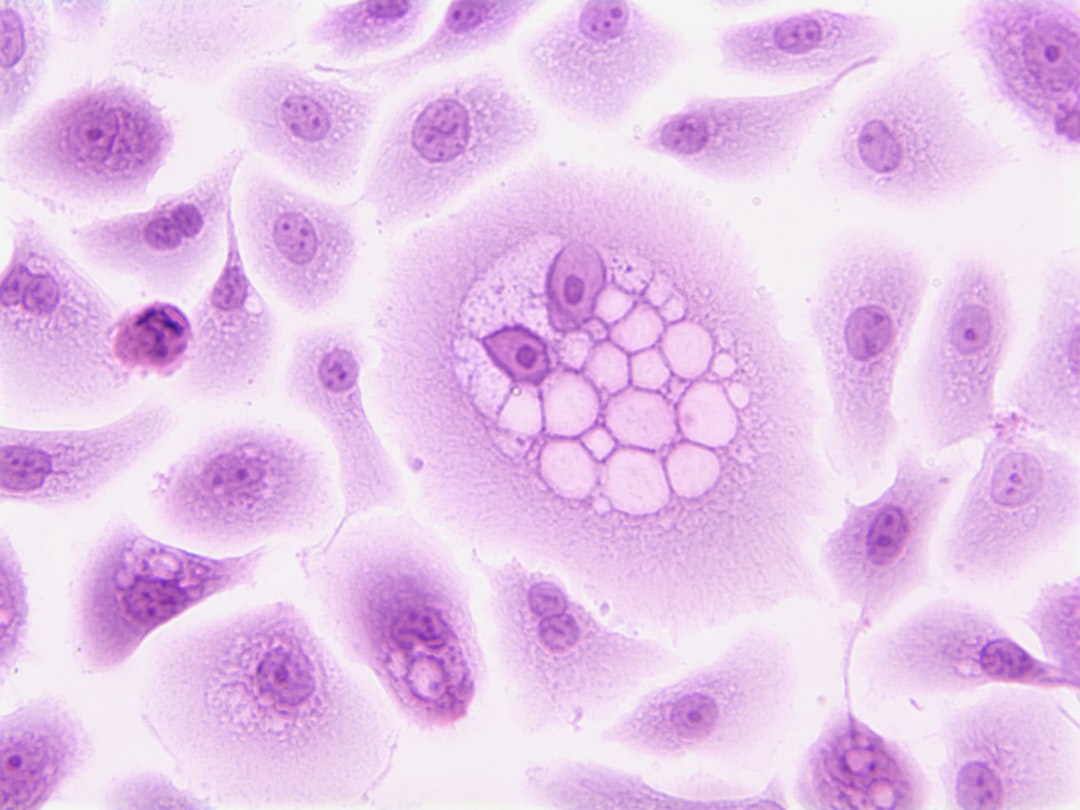

First, it is important to recognize that most of the early work on understanding cancer cells (upon which modern thought rests) were performed in a cultured dish. This fact alone should raise concerns about the applicability of the findings to intact human beings.

For example, for decades it was believed that radiation caused cancer by mutations within cells. Then, it was discovered that new cells added into a culture dish that was previously irradiated also developed mutations. Strange.

Second, we have the problem of cancer arising from carcinogens that are not mutagenic - i.e. no genetic damage. This can be via inflammation, over-excitation, energy and metabolism impairment, fibrosis, etc.

Third, Chester Southam of the Sloan-Kettering cancer center performed experiments in which he implanted people with tumor cells:

Healthy people demonstrated local inflammation that healed within weeks - no cancer

Sick people took longer to heal, still no cancer

People with cancer were very slow to destroy the cells, and sometimes still present until death

Southams work contradicts what can be assumed under the single-cell spreading outward model.

Finally, several additional observations within the cancer literature:

Cells can accumulate hundreds of mutations, and still function normally in the organism

When these cells are separated and grown in a culture dish, their mutagenic differences become apparent

Stem cells transplanted into a tumor become cancerous themselves

Cancerous cells transplanted into mice liver become docile, and adjust to the local environment

As you increase the load of the cancer cells transplanted, the more likely it was that some of these cells would continue its malignant behavior

Probably those cells whose neighbors are not normal healthy tissue

Cancer treatment prognosis depends heavily on hormonal milieu of the human in question - e.g. breast cancer treated in certain phase of menstrual cycle

Environmental causes of inflammation modify risk of cancer occurrence & recurrence

and, so on…

How do we reformulate Cancer?

One simple way to reconcile the genetics vs whole body conundrum is to consider that our genetic snapshot of tissue suffers from a chicken & egg dilemma.

Are we to assume that our genes are not impacted in any way by cellular machinery?

Are those cells not impacted by extracellular events? Or impacted by signals of various fluids, proteins, and electrochemical reactions?

Obviously not.

Then, did the environment lead to changes in genetic expression across the whole organism?

Or, did a mutation in one cell lead the whole body to acquiesce to its demands?

Peat’s Perspective:

His starting point for a cancer model starts with a concept that we even learn in medical school: the whole body plays a role in regulating cancerous cells. He calls this the cancer field.

An easy example concerns warts and moles. These are neoplastic & dysplastic outgrowths from otherwise normal tissue. Why don’t they become cancerous in most people?

Our current model states that our immune system plays a role in suppressing its proliferation, effectively stopping the tumor in its tracks. Peat would suggest that these benign tumors don’t grow out of control because of overall physiology does not support their growth.

Another example is polyps - very common!

You may have heard of polyps in the colon. These polyps are considered high-risk for transformation into malignancy. As such, they are usually removed during a routine colonoscopy.

But, why do they form to begin with?

One answer lies in anemia. For example, people with iron-deficiency anemia are known to have a higher likelihood of developing polyps.

Why?

If you are anemic, your organs and bone marrow will respond by creating new blood cells in hopes of correcting the anemia. This proliferative process tends to also result in soft-tissue outgrowths - particularly those that are highly vascular, such as polyps.

In fact, even ancient teachings of Tibetan medicine suggests a direct relationship between these entities:

Anemia → Corrective Proliferation → Polyps → Malignant Transformation

This perspective is already half-way to Peat’s own view.

For Peat, cancers grow as a result of overstimulation.

When tissue is injured, it releases signals to notify the local environment and the whole body that there is damage which needs to be repaired. Similar changes occur when under stress or inflammation.

The stronger and more continuous the stimulus, the more energy the cell needs.

In some cases, the cells can become desensitized - and survive in the presence of continuous stimulation or irritation. Otherwise, the cells would die when they don’t have enough energy to keep responding.

Cancer cells demonstrate intense stimulation. This is reflected in observations such as increased rate of oxygen consumption, lactic acid production, and hormonal signalling. These cells are, however, energetically inefficient. Their increased energy requirements are beyond the ability of the mitochondria’s capacity.

The excess stimulation depletes glucose, and causes a shift toward consumption of fat and protein. This, in part, accounts for the observation of cancer patients becoming thin and cachectic.

These factors (amongst others) ultimately result in changes in metabolism & tissue repair that develop positive-feedback loops, which can result in the formation of malignant tumors as well as the appearance of metastasis.

There are several other observations, that far exceed the word limit for this article.

I can go into more detail about the relevant biochemical and physiology pathways identified in cancer metabolism - let me know in the comments if you are interested.

What are the Implications?

First, the current practice of oncology:

Without addressing the underlying physiologic milieu of the patient, cancer can never truly be cured

Further, the current treatment paradigm of causing systemic & local damage (chemo & radiation) may only worsen overall disease state

So, how can we approach cancer?

Reduce overstimulation, inflammation, and stress

This will mostly be achieved by lifestyle modification

Medicinally, this can be achieved with hormonal balance, aspirin, and other anti-inflammatories

Provide nourishment for approprite healing & repair

Saturated fats, animal protein, fruits, fresh dairy, etc

General rule of thumb: if it came from rich & fertile ground or healthy animals, it is likely nutrifying

Generate conditions which clear waste & dysfunctional cells

One mechanism to use in our favor would be autophagy

Have confidence in looking beyond the scope of oncology for solutions

There are several alternative approaches to dealing with cancer, many of which have been developed over centuries within other fields of medicine

After decades of research & billions in funding…it is long past due that we consider an alternative framework.

The organism can only be understood in its environments, and a cell can't be understood without reference to the tissue and organism in which it lives.

Although the geneticists were at first hostile to the idea that nutrition and geography could have anything to do with cancer, they soon tried to dominate those fields, insisting that mutagens and ethnicity would explain everything.

But the evidence now makes it very clear that environment and nutrition affect the risk of cancer in ways that are not primarily genetic.

-Ray Peat

If you like this kind of content, drop a comment or send feedback to info@remnantmd.com

A happy and healthy new year to you 😊

I consider myself part of the Ray Peat cult. Practiced his theories for 3 years and dropped 30 points of blood pressure, lost 15lbs, and have far more energy. Even my gray hair has returned some color. Your further thoughts on any Ray Peat topic is of interest.