Germ Theory Is Incomplete | Part 2

After a full year of ruminating on this topic, the time has come for Part 2 of this conversation.

For those who are new here and haven’t read Part 1 of this series, I would highly recommend you read it before proceeding.

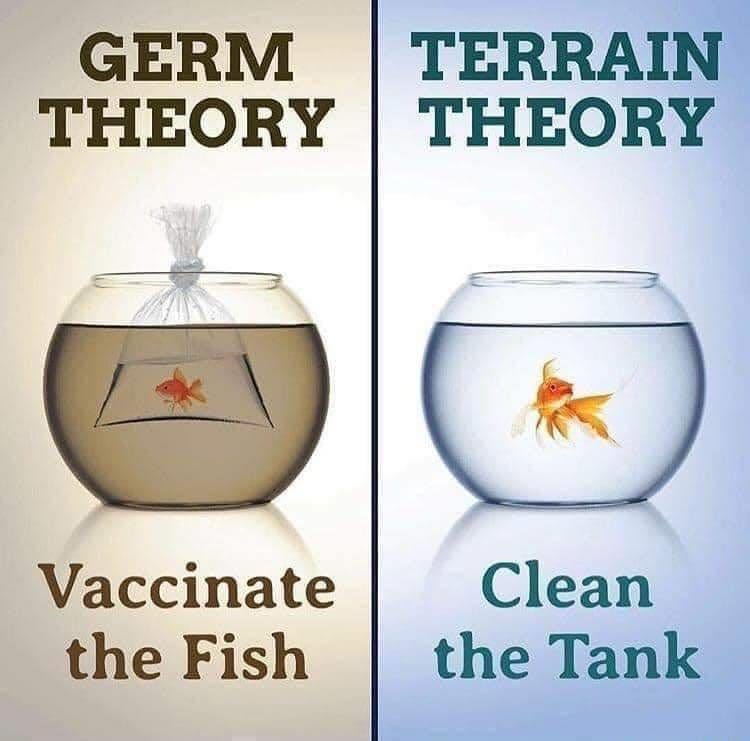

In the first part, we discussed the origins and basic tenets of germ theory, insofar as it aims to prove that certain micro-organisms are the proximate cause of disease. We also discuss how and why this framework falls apart under the slightest scrutiny.

We also discussed Terrain theory, which has been historically presented as the competing model to germ theory. Evidently, a combination of research funding and sociocultural trends have favored a “germ” and “infectious” framework. This is likely why Germ Theory prevailed in the academy as the de facto model to inform Infectious Disease (the medical discipline).

As you may expect, the truth tends to lie somewhere in the middle.

In my opinion, Germ Theory is a special case of Terrain Theory. In other words, these are not mutually exclusive models. Rather, one (germ) is a subset of the other (terrain).

There are two important contentions that arise when I make this statement.

First, what does that even mean?

Second: “But, antibiotics!”

I think what people want to know is, once we understand the role of microorganisms in this new framework, how do we address states of “infection?”

Which are great questions. Let’s dig in.

Germ Theory Is The Special Case

The fundamental framework of germ theory is that disease in humans is caused by the presence/growth of a micro-organism. That is to say, a specific disease’s proximate cause is the presence of a specific microorganism.

For example, one alleged cause of community-acquired pneumonia is streptococcus pneumoniae.

Even with something as common as pneumonia, we immediately encounter a problem. As mentioned in Part 1, our lungs are filled with bacteria and bacterial genomes (important because we typically test for presence of genes when diagnosing these days; see PCR).

The bacteria which are supposed to be the cause of pneumonia (e.g. Haemophilus Influenzae or Strep Pneumoniae) are routinely found in the lungs of people who are healthy and without any clinical symptoms of respiratory dysfunction.

This is the case nearly everywhere you look:

The skin is covered in bacteria.

The GI tract is covered in bacteria, including Clostridium difficile in patients with no gastrointestinal symptoms.

The urinary tract has many bacteria, and is often inappropriately treated as a “urinary tract infection” despite the fact that the patient has no symptoms.

Typically, germ theory apologists will say something like “these are opportunistic infections” or “there are other risk factors for infection.”

But, what they don’t realize is that they are actively making a case for Terrain Theory.

How?

Let’s look at this from the perspective of a specific bacteria. Actually, the example of C. Difficile is very informative here.

If your host’s GI tract experiences a major disturbance, what does this mean from your (C. Diff’s) perspective?

Simple: the environment in which you reside (the colon) has changed. As a result of your environment changing, a new equilibrium develops by an interaction of the resources in the colon and the life-forms which exist in it.

A certain percentage of humans have detectable levels of C. Diff under normal conditions. Typically, a C. diff “infection” arises in people who have received antibiotics which destroy bacterial populations of the gut.

This event signifies a change in the environment (or terrain).

This drastic change in the gut allows bacteria which are more hardy and competitive to flourish. Like Clostridium difficile.

Now, in this example - tell me:

What is the proximate cause of gastroenteritis/diarrhea/toxic megacolon?

Is it the C. diff? Or, the antibiotic which created the conditions for C. diff to grow?

Is it the bacteria at fault? Or, whatever caused a change in the environment? Because, fundamentally the bacteria hasn’t changed.

The bacteria continues to act as it always has. But, the environment has changed.

This is the case with many infectious diseases. ‘Opportunistic infection’ and ‘risk factors’ all account for the same thing.

Something has changed in the host - which is indistinguishable from the environment, from the perspective of the microorganism.

Sometimes the change in the environment allows something that was always there to flourish.

Other times, a change in the environment introduces a new microorganism.

For example, if you cut your skin - you now have a defect in the boundary between the surface of the skin and the soft-tissue underneath. This allows bacteria to move from one environment into another, and initiate an inflammatory response we call cellulitis.

If a surgeon makes an incision, he runs the risk of moving skin-surface bacteria into a deeper cavity of the body. This is why they sterilize the surface before they start cutting.

From the perspective of the micro-organism, this is the same thing.

You can either change the environment the bacteria is already in, or you can move the bacteria into a new environment.

In both cases, the living organisms and resources of this new environment have to arrive at a new equilibrium.

Sometimes, this process results in a strong inflammatory response which threatens the host (human).

How Do We Handle Infections?

This brings us squarely into the conundrum people seem to face with this new perspective.

If we accept this new framework, how do we deal with bacteria?